*Le contenu de cette page n’est pas encore disponible en français. Veuillez accepter nos excuses. Nous espérons vous offrir plus de matériel en français dès que possible.

A class at Lampson Elementary School in Esquimalt.

Source: Image Courtesy of The Greater Victoria School District Archives.Date: [ca. 1914]

Victoria’s education system has always reflected competing identities within the larger community. During the era of Hudson’s Bay Company control, Victoria’s elites sent their children to fee-based Anglican schools, while poor children attended inferior Anglican schools funded by the colony.[1] This system was designed to maintain the hierarchical social order of Britain and the dominance of the Church of England. So rigid was this social hierarchy that the established elites prevented non-conformist[2] settlers from Ontario and the Maritimes, who came to Victoria during the Gold Rush of 1858, from joining their social set. As a result, the newcomers agitated for free, non-denominational schools that all children could attend, and persuaded the majority of settlers that hostility between rich and poor and between different denominations was “inimical to the growth of independence, and so detestable in a young community like our own.”[3] In 1872, free, non-denominational public schooling was established in British Columbia. After Confederation, greater numbers of British Columbians identified public education as a means of social advancement in the new nation.[4]

The new public system flourished in Victoria. The population increased rapidly at the turn of the century, and in 1901, school attendance became mandatory between ages 7 and 14. Consequently, at least one large school was constructed each year prior to WWI.[5] Victoria High, the first public secondary school in B.C. at the time of its construction in 1876, was a source of civic pride.[6] The prestigious architect Francis Rattenbury designed the third Victoria High building completed in 1902, causing the newspapers to boast that “Victoria now has a high school worthy of the capital city of the premier province.”[7] In 1903, Victoria High affiliated with McGill University; after 1907, students could complete the first two years of their arts degree at Victoria College before going to McGill. This arrangement ended when the University of British Columbia opened in 1915, but Victoria High affiliated with UBC in 1920 and again offered first and second year Arts and Science classes.[8]

University School Honours Cap, 1913-1914.

Source: Image Courtesy of St. Michaels University School Archive: 2001.11.20.Date: 1913-1914

Victoria’s private education system also thrived. In the years prior to WWI, Victoria attracted approximately 24 000 elite British families, who wanted the privileged lifestyle they could no longer afford in England.[9] These elites supported private fee-based Anglican schools, such as University School or St. Michaels Preparatory School, to ensure their children received the training befitting their prominent social status, particularly character building for leadership.[10]

Several differences existed between the private and public systems. First, the private system usually had sex-segregated schools, while boys and girls attended public schools together in almost equal numbers.[11] Over one-half of private school teachers had attended Oxford or Cambridge.[12] In comparison, 29 of the 49 teachers appointed to Victoria High between 1876 and 1914 received their degrees at Canadian institutions, among them Arthur Currie. [13]

Dora Atkins, co-founder of Norfolk House School for Girls.

Source: Image Courtesy of Glenlyon-Norfolk School Archives.Date: 1913.

A crucial difference between public and private schools was academics. Private schools taught a traditional curriculum based on Latin, French, and sometimes mathematics, disdaining science as a practical subject suited only to those who had to work for a living. In fact, athletic performance was often valued more highly than academic performance.[14] In contrast, public schools gave all students intensive instruction in English, history and geography, and offered classes in science.[15] Manual training such as carpentry (for boys) and domestic science (for girls) was introduced during the war. [16]

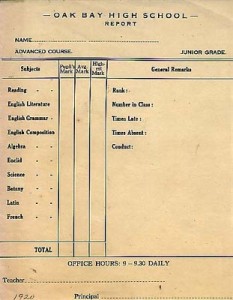

Oak Bay High School Report Card, indicating subjects taught.

Source: Image Courtesy of Oak Bay High School Archives.Date: 1920.

Public school staff and students threw themselves behind the war effort. Military and militia members assessed whether teachers were competent to instruct classes in physical drill, and helped run cadet drills.[17] Students made comforts and wrote letters to soldiers abroad. Some schools fundraised for the Red Cross and other relief efforts with concerts, while others sold vegetables from their gardens; Burnside School students in particular were known as “soldiers of the soil.”[18]

Many boys and male teachers left the education system to fight in the war. Female teachers strove to prove their abilities and fill the void, however, leading one school inspector to warmly note that “it has not so often been necessary to ask for greater effort [from female teachers] as to warn against the danger of overwork.” [19]

Apart from short term exigencies, the war encouraged major conceptual changes in both public and private schooling. As private school children continued to fail the entrance exams necessary to commence public high school, headmasters increasingly realized that their alumni’s skill sets did not match the needs of the new technical Canadian society, and began to follow provincial curriculum.[20] Public schools became a little more Canadian as well: the war had resulted in a celebration of Canadian soldiers, and textbooks began to stress an increasing sense of autonomy. “In her relations with the foreign countries,” one textbook stated, “Canada has become less and less dependent on the motherland…As an independent member she signed the Treaty of Peace and was enrolled in the League of Nations.”[21] The war had hastened the evolution of Victoria’s education system between 1872 and 1921 as it slowly began to reflect B.C.’s shifting role within the Empire and the Dominion.

By Hannah Anderson

[1] A few sent their children to reputable fee-based Catholic schools, such as St. Ann’s Academy.

[2] Non-conformists are Protestants who do not accept the rites of the Church of England, and believe personal conversion is more important for salvation than religious ritual. For instance, Methodists and Presbyterians are non-conformists. Some historians also refer to these Protestants as evangelicals. See Jean Barman, “Transfer, Imposition or Concensus? The Emergence of Educational Structures in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia,” in Schools in the West: Essays in Canadian Educational History, ed. Nancy M. Sheehan, J. Donald Wilson and David C. Jones (Calgary, AB: Destselig Enterprises, 1986), 245-236.

[3] The Colonist, April 13, 1865, quoted in Jean Barman, “Transfer, Imposition or Concensus?,” 248.

[4] Jean Barman, Growing Up British in British Columbia: Boys in Private School (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1984), 7.

[5] Douglas Franklin and John Fleming, “Early School Architecture in British Columbia: An Architectural History and Inventory of Buildings to 1930,” (Victoria, B.C.: Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services, Heritage Conservation Branch, 1980), 10, 88; “1913: 100 Years Ago in Victoria,” Times Colonist 17 March 2003, page 47. Patricia E. Roy, Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012), 96.

[6] Jean Barman, Transfer, Imposition or Concensus?,” 7, 242-257.

[7] This high school building was later demolished. Oak Bay and Esquimalt School Districts were also building modern sophisticated schools. Saanich schools were still quite rural, and belonged to several separate districts: Sidney School District, North Saanich School District, and Deep Cove School District. “1913: 100 Years in Victoria,” Times Colonist 17 March 2003; Franklin and Fleming, “Early School Architecture,” 85-86; “Hundred Years of Learning,” Daily Colonist 21 March 196, 6-7. Ron Baird, Success Story: The History of Oak Bay, (Victoria, B.C.: Daniel Heffernan, James Borsman Publishers, 1979), 123; The Forty-Third Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1913-1914 by the Superintendent of British Columbia (Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty), A34.

[8] Smith, Come Give a Cheer!, 26-28. Fourty-Fourth Annual Report of the Public Schools, A45.

[9] Jean Barman, Growing Up British, 2.

[10] Ibid., 14, 18-21, 64-65.

[11] The exceptions are Boys Central School and Girls Central School. Dan Robert Hawthorne, “Patterns of 20th Century Attendance: A Systematic Study of Victoria Public Schools, 1910-1921” (MA Thesis, University of Victoria, 1985), 75-77.

[12] Ibid., 44.

[13] Fourty-Fourth Annual Report of the Public Schools, A25.

[14] Jean Barman, Growing Up British, 67-69.

[15] R.D. Gidney and W.P.J. Millar, How Schools Worked: Public Education in English Canada, 1900-1940 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012), 218.

[16] The Fourty-Fourth Annual Report of the Public Schools, A43-44; Peter Smith, Come Give a Cheer!, 76.

[17] Alexander Robinson, The Forty-Fifth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1915-1916 By the Superintendent of Education. (Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty,) A45, A47.

[18] Fred Holm, “Manual Training in Early Victoria,” The Daily Colonist, Sunday April 2, 1978, pages 10-11.

[19] Alexander Robinson, The Forty-Sixth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1916-1917, D25.

[20] Barman, Growing up British, 67-68.

[21] Gammell, History of Canada (Toronto: Gage, 1921), quoted in Harro Van Brummelen, “Shifting Perspectives: Early British Columbia Textbooks from 1872 to 1925,” in Schools in the West: Essays in Canadian Educational History, ed. Nancy M. Sheehan, J. Donald Wilson and David C. Jones (Calgary, Alberta: Detselig Enterprises Limited), 27.

Archives

Victoria High Archives.

Oak Bay High Archives.

Willows School Archives.

Sisters of St. Ann Archives.

Greater Victoria School District Archive.

City of Victoria Archives.

British Columbia Archives

Bibliography

Baird, Ron. Success Story: The History of Oak Bay. Victoria, B.C.: Daniel Heffernan, James Borsman Publishers, 1979.

Barman, Jean. Growing Up British in British Columbia: Boys in Private School. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1984.

Barman, Jean. “Transfer, Imposition or Concensus? The Emergence of Educational Structures in Nineteenth-Century British Columbia.” In Schools in the West: Essays in Canadian Educational History, edited by Nancy M. Sheehan, J. Donald Wilson and David C. Jones, 241-264. Calgary, AB: Destselig Enterprises, 1986.

Brummelen, Harro Van. “Shifting Perspectives: Early British Columbia Textbooks from 1872 to 1925.” In Schools in the West: Essays in Canadian Educational History, edited by Nancy M. Sheehan, J. Donald Wilson and David C. Jones, 17-38. Calgary, AB: Destselig Enterprises, 1986.

Franklin, Douglas and John Fleming. “Early School Architecture in British Columbia: An Architectural History and Inventory of Buildings to 1930.” Victoria, B.C.: Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services, Heritage Conservation Branch, 1980.

Gidney, R.D. and W.P.J. Millar. How Schools Worked: Public Education in English Canada, 1900-1940. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Hawthorne, Dan Robert. “Patterns of 20th Century Attendance: A Systematic Study of Victoria Public Schools, 1910-1921.” MA Thesis, University of Victoria, 1985.

Roy, Patricia E. Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2012.

Smith, Peter L. Come Give a Cheer! One Hundred Years of Victoria High School, 1876-1976. Vancouver: Evergreen Press, 1976.

The Forty-Third Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1913-1914 by the Superintendent of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1915.

The Forty-Fourth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1914-1915 by the Superintendent of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1916.

The Forty-Fifth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1915-1916 by the Superintendent of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1917.

The Forty-Sixth Annual Report of the Public Schools of the Province of British Columbia 1916-1917 by the Superintendent of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C.: The Government of British Columbia, Printed by William H. Cullin, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1918

Newspaper Articles:

“1913: 100 Years Ago in Victoria,” Times Colonist 17 March 2003, page 47.

“Hundred Years of Learning,” Daily Colonist 21 March 196, 6-7.

Fred Holm, “Manual Training in Early Victoria,” The Daily Colonist, Sunday April 2, 1978, pages 10-11.

Further Reading

A Chaplet of Years: St. Ann’s Academy: to the pupils past and present of the Sisters of St. Ann, Victoria, B.C., 1858-1918. Victoria, B.C.: Colonist Print. And Publishing. [1918?]

Barman, Jean and Mona Gleason. Children, Teachers and Schools in the History of British Columbia. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises, 2003.

Calam, John. “Teaching the Teachers: Establishment and Early Years of the B.C. Provincial Normal Schools.” BC Studies 61 (Spring 1984): 30-63.

First 100 Years: Metchosin Elementary School.(Victoria City Archives)

Fleming, Thomas. “In the Imperial Age and After: Patterns of British Columbia School Leadership and the Institution of Superintendency, 1849-1988.” BC Studies 81 (Spring 1989): 50-76.

Fleming, Thomas, ed. School Leadership: Essays on the British Columbia Experience, 1872-1995. Mill Bay, B.C.: Bendall Books, 2001.

Humphries, Charles W. “The Banning of a Book in British Columbia.” BC Studies no. 1 (Winter 1968/1969)

Lai, David-Chun. “The Issue of Discrimination in Education in Victoria, 1901-1923.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 1987.

Martens, Margaret Milne and Graeme Chalmers. “Educating the Eye, Hand and Heart at St. Ann’s Academy: A Case Study of Art Education for Girls in Nineteenth-Century Victoria.” BC Studies 144 (Winter 2004/2005): 31-59.

Patricia Dickinson. Reminiscences of Saint Ann’s, Victoria, B.C. 1858-1973. Winnipeg: National School Services, 1983. UVic Special Collections.

Scott, Winifred and Keith Walker. Do Thy Best: An Informal History of Norfolk House School, 1913-1986. Victoria, B.C.: Glenlyon-Norfolk School, 2003.

South Park School: Memories Through the Decades. Victoria City Archives.

Stanley, Timothy J. “White Supremacy, Chinese Schooling, and School Segregation in Victoria: the Case of the Chinese Students’ Strike, 1922-1923.” Historical Studies in Education, 1990.

Sutherland, Neil. Children in English-Canadian Society: Framing the Twentieth Century Consensus. Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2000.

Sutherland, Neil. Growing Up: Childhood in English Canada from the Great War to the Age of Television. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

St. Ann’s Academy: Diamond Jubiliee Number: 1858-1933. Victoria, B.C.: J. Parker Buckle Printing Co. Ltd.