Coast and Straits Salish Peoples in Victoria

*Le contenu de cette page n’est pas encore disponible en français. Veuillez accepter nos excuses. Nous espérons vous offrir plus de matériel en français dès que possible.

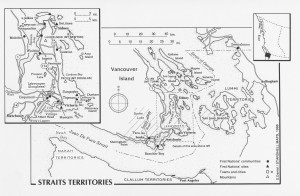

The area that we now know as Greater Victoria is the traditional territory of the Saanich, Esquimalt, Songhees, Sooke, and Beecher Bay bands. Because a prominent village site was located on the inner harbour, the Songhees band of the Lekwungen People were perhaps the

most visible of these groups at the onset of the war. Despite having treaty rights to the reserve on the inner harbour, the Lekwungen faced pressure to move from the village as early as 1858. Many Victorians recognized the inner harbour as an increasingly valuable commercial area but all attempts to move the Songhees were blocked until 1910.[1]

In 1910, the Lekwungen, led by Chief Michael Cooper, completed negotiations with the provincial and federal governments to move from the inner harbour to land near the Navy base in Esquimalt harbour. They finalized the agreement in the spring of 1911 and 44 family heads recognized in the negotiations were granted payment for the move.[2] Less than a year later, the homes on the old reserve were destroyed to make way for new building.[3]

In other parts of Canada, Ontario in particular, many Aboriginal men enlisted to serve in the First World War, though, after 1915, recruiters accepted fewer into service.[4] An official from the Department of Military and Defense argued that Aboriginal men be refused enlistment because “while British troops would be proud to be associated with their fellow subjects… Germans might refuse to extend to [Indigenous Peoples] the privileges of civilized warfare.”[5] Some recruiters weighed arguments like the above heavily and others less so, resulting in inconsistent enlistment of Aboriginal soldiers across Canada. In addition to enlistment barriers, Aboriginal soldiers often faced institutional racism that barred them from advancing to commissioned ranks and made trench life more unbearable.[6] Later in the war, the Ministry of Militia changed their policies to reflect the dire need for replacement soldiers by actively recruiting Aboriginal men, especially for forestry and construction battalions.[7]

Statistically, fewer Aboriginal men enlisted in British Columbia than in other areas of Canada.[8] In addition to policies that excluded them, low enlistment was likely due to culturally reinforced racial prejudice that was not confined to B.C., but was entrenched and vocal in the West. In March of 1917, for example, a protest staged in B.C. responding to the proposed integration of Aboriginal men into existing non-Aboriginal units.[9] Other local grievances included the potlatch ban. The potlatch was banned in 1885, but the ban was rarely enforced and potlatch continued to be a culturally and socially significant activity. Due to the more repressive climate after 1908, local authorities began to prosecute potlatch participants more often. This was supported by the Department of Indian Affairs, who constructed a wartime argument that potlatch was wasteful and unpatriotic.[10] The combination of federal policies and local tensions were likely the cause of lower enlistment among Aboriginal men and women from the Victoria area.

To view a list of Canadian Aboriginal veterans see The Aboriginal Veterans List. This website allows you to search for veterans by geographical area or by name. You will see that many Coast Salish and Saanich soldiers from the Greater Victoria area served in the Canadian military during World War II and after. While this site lists no First World War veterans, determining Aboriginal heritage is difficult from the attestation records used in this project. If you have any information regarding Aboriginal veterans from the Victoria area, please contact this project at jimk@uvic.ca.

The Annual Reports of the Department of Indian Affairs focus on the participation of Indigenous communities in the war effort on the homefront. They highlight the fundraising efforts of First Nations that helped support the Red Cross, Patriotic Fund, and other war support systems. Reports also mention the efforts of Aboriginal women in making bandages and knitting, as were common duties asked of all Canadian women. You can view the Annual Reports on the Archives Canada website or see exerts in our document archive.

By Ashley Forseille

[1] John Sutton Lutz, Makúk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 88-89.

[2] Grant R. Keddie, Songhees Pictorial: A History of the Songhees People as Seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912 (Victoria: Royal BC Museum, 2003)¸146.

[3] 154

[4] Fred Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers (Penticton, B.C.: Theytus Books, 1985), 7.

[5] Cited in Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 6 from RG 24, Vol. 1221, File 452-13.

[6] Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 20.

[7] Timothy Winegard, For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2012), 106.

[8] Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 9.

[9] Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 21.

[10] Lutz, Makúk, 106

Sources:

Aboriginal Veterans Tribute List. http://www.vcn.bc.ca/~jeffrey1/tribute.htm (accessed 28 July 2013).

Gaffen, Fred. Forgotten Soldiers. Penticton, B.C.: Theytus Books, 1985.

Keddie, Grant R. Songhees Pictorial: A History of the Songhees People as Seen by Outsiders, 1790-1912. Victoria: Royal BC Museum, 2003.

Lutz, John Sutton. Makúk: A New History of Aboriginal-White Relations. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Winegard, Timothy. For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2012.

Further Reading:

Dempsey, James. Warriors of the King: Prairie Indians in WWI. Regina, SASK: University of Regina, 1999.

Moses, John. A Sketch Account of Aboriginal Peoples in the Canadian Military. Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 2004.

Talbot, Robert J. “’It Would Be Best to Leave Us Alone’: First Nations Responses to the Canadian War Effort, 1914-18.” Journal of Canadian Studies45.1 (Winter 2011): 90-120.

Walker, James W. “Race and Recruitment in World War I: Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.” Canadian Historical Review 70.1 (1989): 1-26.

Winegard, Timothy. Indigenous Peoples of the British Dominions and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.