Victoria in the “Air Age”: Aviation in the Capital, 1910-1925

*Le contenu de cette page n’est pas encore disponible en français. Veuillez accepter nos excuses. Nous espérons vous offrir plus de matériel en français dès que possible.

Learn more about aviation in Victoria here

In September, 1909, a strange machine floated through Victoria’s skies – an American airship, the first aerial craft to fly over British Columbia.[1] The Air Age had arrived.

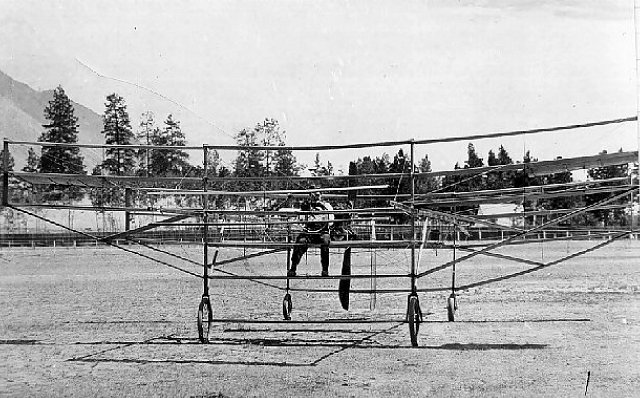

William Wallace Gibson at the controls of his twin-plane. Courtesy of the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum.

When that American airship drifted into view, one of Victoria’s citizens was already hard at work on what would become the first aircraft designed and flown by a Canadian. William Wallace Gibson, born near Regina, Saskatchewan, had been experimenting with flying devices since his childhood. He came to the West Coast in 1906, made a small fortune prospecting, and promptly retired to his workshop, eager to start work on his very own airplane. Years of work produced the “twinplane,” a very unorthodox machine that first took to the air on September 8, 1910, with Gibson at the controls. Today, a small cairn on Richmond Road commemorates this very big event in the aviation history of Canada.

The early years of the Air Age saw several other exciting events take place in the skies over Victoria. In late May, 1911, the city’s schoolchildren were given a special holiday so that they could join the crowd watching American pilot Charles F. Walsh, who flew his Curtis-Farman biplane for fifteen minutes and reached 600 feet in altitude, setting a new record for highest and longest flight made over Vancouver Island.[2] A year later, Canadian Billy Stark was contracted to fly in the city’s Victoria Day celebrations.[3] Then, on August 6, 1913, Victoria became the site of the first fly-by over the core of a British Columbian city – and Canada’s first aviation fatality. American pilot Johnny Bryant was just passing City Hall when he lost control of his Curtiss biplane. The aircraft “dashed down” into the roof of a nearby building “with a crash that could be heard for several blocks.”[4] Bryant died on impact.[5]

During the early 1910s, Victorians laughed, cheered, and gasped as brave pioneers took to the air. Soon, the possibilities of flight were to be tested in the most rigorous way imaginable: as of August 4th, 1914, Canada was at war with Germany, and a new phase in aviation history had begun.

Airplanes proved to be incredibly valuable on the Western Front, gathering vital intelligence on German positions, engaging enemy aircraft, and supporting ground troops with machine gun fire and small bombs. As the Dominion did not have an air force of its own until the last two months of the war,[6] Canadians who wished to follow in the footsteps of flying aces like Billy Bishop and Raymond Collishaw joined the British Royal Flying Corps, originally formed in 1912, or the Royal Naval Air Service, which split from the RFC a few months before the war began. There were quite a few young men from Victoria who took part in the world’s first aerial war. Most transferred into the RFC or RNAS from the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Some, however, enlisted directly in the air forces, joining up with the recruiters who worked out of the city’s Post Office.

While many pilots felt that it “was a lot better to be flying up above all the battles” than to be in the trenches,[7] theirs was still a very dangerous job, and casualties were high.[8] Some of Victoria’s war pilots were still flying in 1918, when the RFC and RNAS were merged to form the Royal Air Force. Shortly thereafter, the Canadian government made its first proper effort to establish a Canadian Air Force. By the time that the CAF was organized, however, the war had come to an end. Over the course of that conflict, the technology of flight had evolved at an astonishing rate. The rigours of aerial “dogfights” and military reconnaissance had prompted the development of sturdier, faster, and more powerful machines, capable of travelling vastly greater distances and reaching the heights that William Wallace Gibson and other aviation pioneers had only dreamed of. These new aircraft had shown their worth in war; now, aviation enthusiasts had to convince the public and the government that they had a place in peacetime as well.

The R.F.C. and R.A.F. “wings” worn by Second Lieutenant Victor R. Pauline. Courtesy of the British Columbia Aviation Museum.

Many pilots displayed their skills to Victoria’s citizens in the first few years after the Armistice. On May 13, 1919, Captains Alfred Eckley and Ernest Hall touched down in Victoria, having just finished the first flight between the mainland and Vancouver Island.[9] That year also saw the establishment of the Victoria branch of the Aerial League of Canada. This group organized “aerial meets” over Willows Camp and the first air mail runs out of Victoria. Starting in October, 1920, the city began to send and receive loads of air mail from Seattle on a daily basis, carried in a C3 Boeing seaplane flown by Eddie Hubbard, an American pilot.[10] On the 17th of that month, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Tylee and Captain G.A. Thompson of the Canadian Air Force landed in Victoria’s Uplands neighbourhood, completing their leg of the first trans-Canada flight.[11] Tylee, Thompson, and the other four pilots who took part in that incredible expedition had had to navigate regions that had never been charted or flown over before, facing terrible weather and mechanical trouble along the way – but they had shown that it was possible to fly across the vastness of Canada.

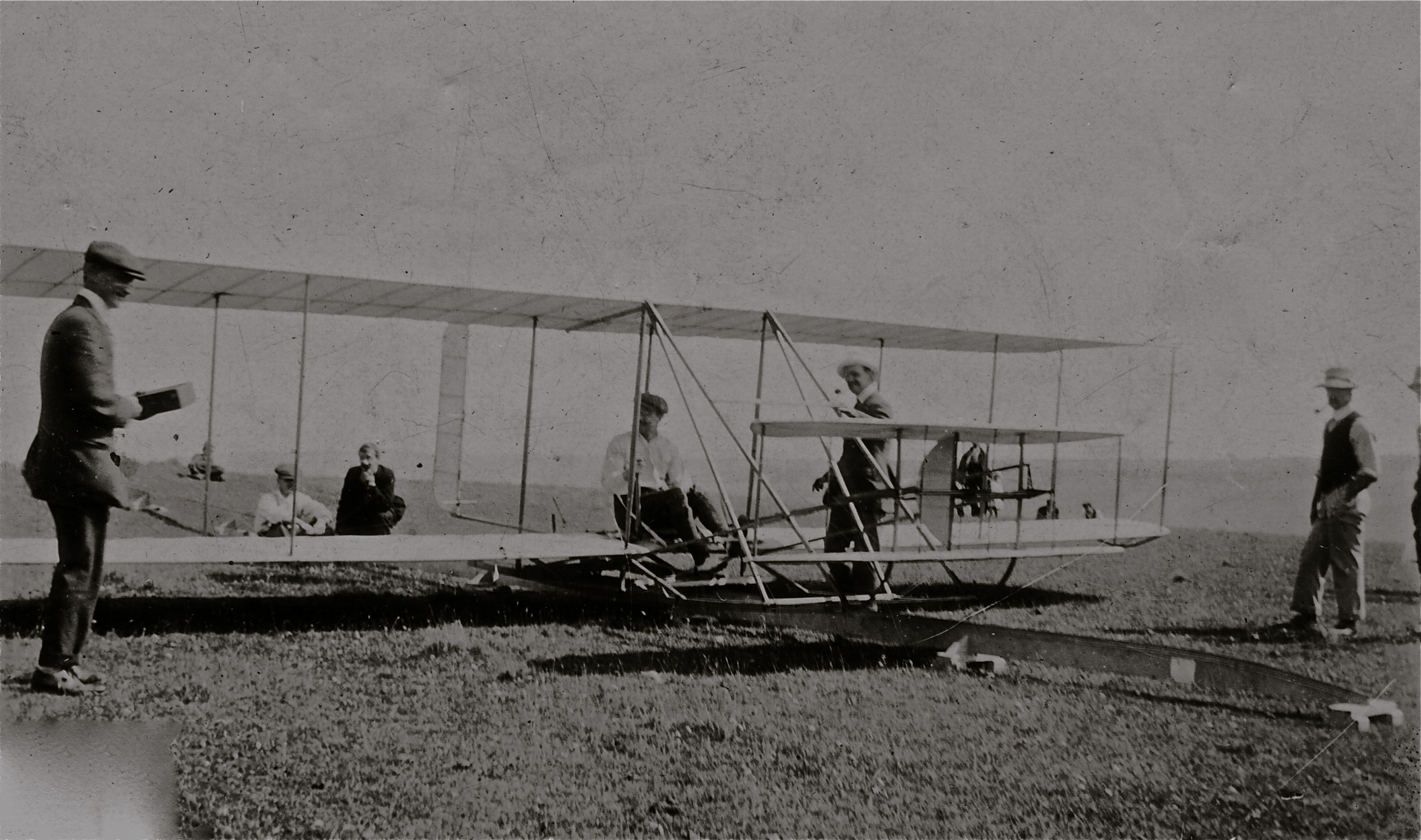

A plane at Willows Fairground in 1919. Restricted for research purposes. Permission of Oak Bay Archives required for commercial use.

Unfortunately, aviation was not yet profitable enough to attract the customers and investors that this industry needed in order to thrive. Most civilian flying companies and clubs spent the early 1920s struggling to make ends meet, and many, like Victoria’s Commercial Aviation School, were forced to close their doors after expensive accidents.[12] Still, the skies over British Columbia’s coast were not empty during these years. Eddie Hubbard made thousands of trips across the Juan de Fuca Strait, flying mail from Victoria to Seattle.[13] On April 1, 1924, the Royal Canadian Air Force was formed, with its No. 1 (Operations) Squadron stationed at Vancouver’s Jericho Beach. From here, the RCAF organized aerial surveys, dispersed chemical agents to tackle pests, and helped the Royal Canadian Navy, based in Esquimalt, to patrol the area’s fisheries. During these years Victoria’s Lansdowne airstrip remained “the only landable airport” on Vancouver Island,[14] welcoming the planes of coastal flying companies and Canada’s newly established air force.

In 1910, Victoria’s citizens scoffed as William Wallace Gibson slaved over his planes. At that time, flying machines were considered the stuff of fiction, a laughable, impossible dream – yet only a decade later, aviation had become a thrilling reality. Aircraft evolved quickly over the next decade, their development spurred by their usefulness above the battlefields of the First World War. After the Armistice, Victoria’s skies buzzed with activity as civilian enthusiasts and returning war pilots continued to test the limits of their skills and their machinery. A considerable number of Victorians participated in this exciting period of aviation history, becoming innovators and pilots; others watched, witnesses to the madness and the wonder of flight.

By Kirsten Hurworth

Notes

[1] Frank H. Ellis and Mary F. Williamson, Canada’s Flying Heritage (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980), 58.

[2] Ibid., 78.

[3]Ibid., 86.

[4] Daily Colonist, August 8, 1913, quoted in David Parker, “”Through Space Suspended”: The First Flights in British Columbia,” in The Magnificent Distances: Early Aviation in British Columbia, 1910-1940, eds. Dennis Duffy and Carol Crane (Victoria: Sound and Moving Image Division, Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1980), 8.

[5] Ellis and Williamson, Canada’s Flying Heritage, 99-101, and Parker, “Through Space Suspended,” 8.

[6] Canada’s first air service, the Canadian Aviation Corps, was formed on September 16, 1914. This force amounted to three men, none of whom were trained pilots, and one American-made Burgess-Dunne bi-plane. The CAC never saw action, and was disbanded by May, 1915. “Canadian Aviation Through Time,” Canadian Aviation Museum.

[7] Thomas Sehl, interviewed by Chris D. Main, September 22, 1978, Side 1.

[8] For a detailed description of a pilot’s life, listen to Lancelot de Saumarez Duke, interviewed by Chris D. Main, August 24, 1978, Side 1.

[9] Ellis and Williamson, Canada’s Flying Heritage, 155.

[10] Parker, “Through Space Suspended,” 13.

[11] Ellis and Williamson, Canada’s Flying Heritage, 185, and “The First Trans-Canada Flight,” Canadian Aviation Through Time.

[12]Parker, 13.

[13]Ellis and Williamson, 157.

[14]Ted Cressy, quoted in “The First Airfields,” in Parker, The Magnificent Distances, 35.

Local Museums and Historic Sites