*Le contenu de cette page n’est pas encore disponible en français. Veuillez accepter nos excuses. Nous espérons vous offrir plus de matériel en français dès que possible.

Learn more about the militia in the digital archive Like most Canadian cities, Victoria was not home to many professional soldiers in the early years of the twentieth century; instead of looking to regular troops for protection, the city turned to their local militia. A militiaman was a “citizen soldier,” a part-time volunteer who enlisted for a term of three years. During that time he was obliged to serve if his unit was mobilized for military service, and to attend twelve days of training per year, for which he would be paid 50 cents a day – significantly less than he would receive for just about any other kind of labor. [1] Serving in the militia was obviously not about making money. Rather, citizen soldiering was an opportunity for social advancement, recreation, and camaraderie, as well as a chance to demonstrate one’s patriotism, good citizenship, and “manly” qualities.[2] Another appealing feature of the militia, for many Victorians, was its Britishness – which was especially pronounced in Victoria, where ties to the mother country ran deep. Still, these attractions were not always enough. For much of the city’s history, Victorians only paid attention to the local militia when trouble was brewing. The first unit to be founded in the city did not survive; the second, the 5th (BC) Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery, managed to scrape by, largely thanks to the generosity of its members, who paid into a “general subscription” so that the unit could afford basic supplies, “rent, fuel, and pay of instructors.”[3] At times, they could not even afford to maintain the fences surrounding their batteries. The general public did not seem terribly concerned; indeed, the regiment complained of livestock being let to “range over the parapets and tramp them down,” and of “mischievous persons” sneaking in to “fill the guns with sticks and stones.”[4]

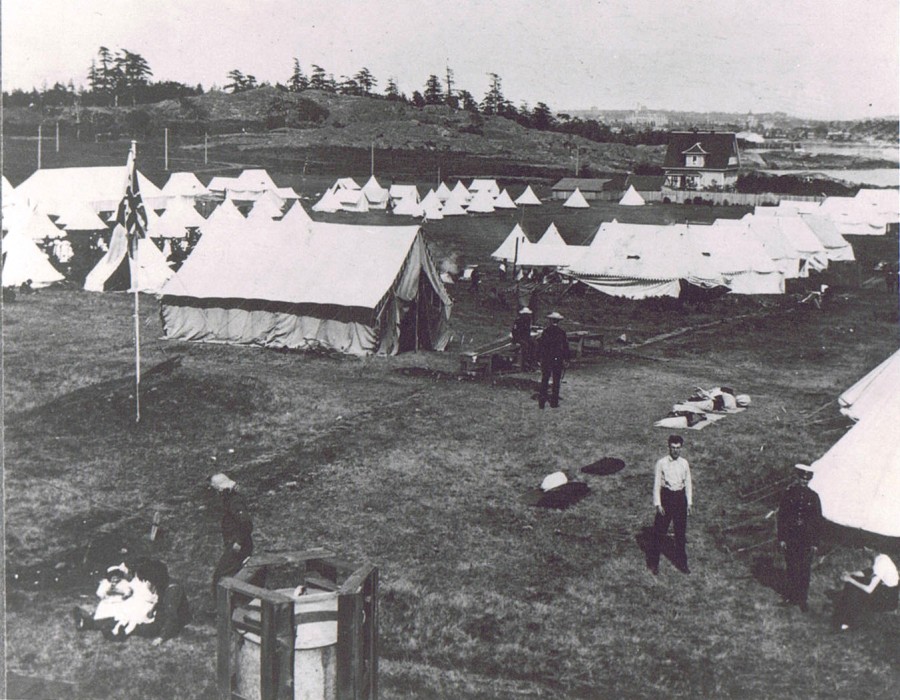

A scene from a militia camp at Macaulay Point. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

This unfortunate state of affairs began to change as the nineteenth century came to an end. From the late 1890s to the outbreak of the First World War, the residents of Victoria started to take an unprecedented interest in the state of their city’s militia. This new enthusiasm was inspired by a variety of recent political developments and powerful personal sentiments, including concern over the increasingly aggressive stance and military expansion of Imperial Germany, personal ties to Great Britain, and the pride that Victorians felt in both the martial prowess of the young Dominion, demonstrated during the campaigns of the Boer War, and the incredible economic and demographic boom that was taking place in British Columbia at that time. The province and its capital had entered an “age of confidence,”[5] and so too did its militia, which expanded rapidly during these years. In addition to the gunners of the 5th Regiment, the city gained two infantry units. The first to be formed was the 88th Regiment, Victoria Fusiliers, established on September 3, 1912.[6] The second, the 50th Regiment of Foot, Gordon Highlanders of Canada, was created on August 15th, 1913, equipped out of the pockets of Victoria’s proud Scottish community.[7]

During these years, the militia was not only growing, but evolving. In earlier times, militia units had had to focus primarily upon the social aspect of their activities, providing a variety of recreational opportunities in the hopes of attracting and keeping recruits. The events of the Boer War prompted a significant change. The glorious successes of Canadian troops at famous battles like Paardeberg and Leliefontein sent a wave of enthusiasm for all things military sweeping across the country, and caused militia enthusiasts to rethink how the nation’s volunteer forces were trained.[8] Victoria’s militiamen were soon spending their yearly twelve-day training camp taking part in more elaborate and practical exercises, such as orchestrating the defence of the forts of Esquimalt or other local landmarks. It was during these exercises that Arthur Currie, the future Commander of the Canadian Corps, received his first experience of command in the field.[9]

Arthur Currie (far right) and friends enjoying a break on 4 Mile Hill, View Royal. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

Currie and his fellow citizen soldiers were only called upon to make use of this military training on one occasion during these years. In the summer of 1913, Victoria’s militiamen were sent up island to Extension, near Nanaimo, to put down a destructive miners’ strike. The worst was over by the time the militia arrived, leaving the strike-breaking force to track down suspected rioters and clean up an astounding amount of property damage. Besides their increasingly advanced military training, Victoria’s citizen soldiers participated in a variety of ceremonial duties and social pursuits. It was common practice for officers to buy their men a round or two of drinks at the end of a training day. Militiamen also socialized over meals in the regimental mess.[10]Occasionally, they would have the honour of guarding visiting dignitaries or attending prestigious events. Local gunners and infantrymen also participated in local, national, and international competitions, winning awards in everything from tug of war to marksmanship. A good showing at these tournaments enhanced a unit’s reputation, and excited even greater interest in the militia, as did parades, band performances, and sports matches between regimental and civilian teams.[11] In these golden days, Victoria’s citizen soldiers enjoyed a new prominence in their community, and became a greater part of the city’s social life than ever before.[12]

The 5th Regiment on parade in downtown Victoria. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

Yet dark clouds were gathering on the horizon. When the storm broke and war began in Europe, local units responded quickly. They had already been preparing for a couple of days, organizing the city’s defenses and putting together lists of volunteers for overseas service. Detachments of militiamen soon reported for duty at Victoria’s coastal batteries and forts. Others patrolled the training grounds at Willows Camp, or guarded the residences of local officials and “vulnerable points” that might be targeted for sabotage, such as railway bridges, the dockyards of Esquimalt, fuel and ordinance supplies, and the telegraph cable station at Bamfield.[13] Over the next four years, the city’s militia forces continued to train, man Victoria’s defences, and supply recruits for units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force that were assembling at Willows Camp. Whether they served at home or overseas, the conflict in Europe impacted each and every one of them – and the institution to which they belonged.

Volunteers from the 5th Regiment leaving for Petawawa as part of the 15th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery. Original notes name them, from left to right, as Ross, Pellow, Patterson, Christensen, and Ware. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

The end of the First World War saw the return of Victoria’s “usual apathy” [14] regarding the militia and its needs. With so many mourning loved ones or caring for wounded veterans, there was little appetite for martial pursuits of any kind in the post-war years. Few returning soldiers were interested in taking up arms again, though some did re-enlist with their old units, returning to the life of sham fights and shooting practice. These military exercises were soon hampered by deep cuts to the militia’s government funding. Still, Victoria’s militiamen trained as best they could, and continued to offer the city’s residents a variety of social outlets, hosting dances, sports events, and other activities. On March 15, 1920, the Victoria Fusiliers and the Gordon Highlanders were reorganized to form the Canadian Scottish Regiment and carry the battle honours of the 16th Battalion a distinguished CEF unit to which both regiments had contributed.[15] The 5th Regiment persisted, and now shares the Bay Street Armoury with the Canadian Scottish Regiment (Princess Mary’s). Today, these units are part of the Reserve Force of the Canadian Army. Theirs is a history of service and fellowship, ambition and discipline, strength and resilience. It is a legacy to be proud of. By Kirsten Hurworth

Notes