Learn more about the coastal batteries in the digital archive

When Canada went to war on August 4th, 1914, Victoria’s coastal defences were nearing the end of a significant growth spurt. The capital of British Columbia had begun to develop its defensive works in 1878, when the city’s first gun emplacement, or battery, was established on Macaulay Plain.[1] Since then, international tensions and local concerns had prompted the establishment and expansion of fortifications in and around Victoria, as well as a local militia unit, the 5th (British Columbia) Regiment Canadian Garrison Artillery.

The British government gave Victoria’s defensive projects valuable support during those early years, sending the city its first artillery pieces and, in 1893 and 1894, a small group of Royal Marines and Royal Engineers.[2] The contributions of these British regulars were considerable. The Royal Marines provided the gunners of the 5th Regiment with advanced technical and military training,[3] while the Royal Engineers helped local laborers to expand Victoria’s coastal defences in accordance with an ambitious new plan, the costs of which were to be shared between the governments of Great Britain and Canada. These improvements included the installation of four new batteries around the city, the placement of electric harbour lights, and upgrades to the established fortifications at Duntze Head, Macaulay Point, and Fort Rodd Hill.[4]

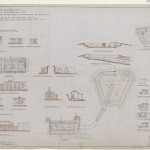

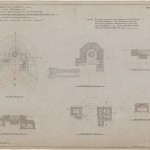

- Plans for Signal Hill Battery

- Plans for Macaulay Point Battery

- Plans for Macaulay Point Battery

Plans for new facilities and artillery installations at Signal Hill and Macaulay Point. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada.

The Royal Marines said farewell to Victoria in 1899, when their five year engagement expired; they were replaced by another, larger group of British regulars who continued to work with the 5th Regiment. The Royal Engineers stayed on, completing the new batteries at Belmont, Black Rock, and Duntze Head by 1904. Signal Hill, the final battery, remained unfinished. Victoria’s new artillery pieces ranged in size and power from the 6-pounder Hotchkiss guns at Duntze Head to the planned 9.2-inch breech-loading guns at Signal Hill. Fort Rodd Hill and Macaulay Point both received “disappearing” guns, mounted on hydro-pneumatic carriages.[5] When they were installed, these weapons were very modern indeed – and by the turn of the century, the men who fired them belonged to one of the largest and most highly trained militia units in Canada. The 5th Regiment gathered regularly to practice at its new batteries, and won numerous accolades at artillery competitions held in Canada and Great Britain. Meanwhile, Victoria became home to two new Permanent Force units; although the British regulars stationed in the city were withdrawn in 1906, a handful of officers and ranks chose to stay, establishing 5 Company, Royal Canadian Garrison Artillery, and 3 (Fortress) Company, Royal Canadian Engineers.[6]

Members of the 5th Regiment with one of their artillery pieces. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

Members of the 5th Regiment with one of their artillery pieces. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.This was the state of Victoria’s coastal defences in late July, 1914, when the British government instructed the Dominion of Canada to prepare for war with Germany. The 5th Regiment started to organize the city’s defences on August 2nd. When war was declared two days later, the regiment quickly moved its headquarters to Work Point Barracks and manned the batteries at Belmont, Black Rock, Duntze Head, Fort Macaulay, and Fort Rodd Hill. 5 Company RCGA took up its post at Signal Hill. Victoria’s defenders were ready, anxiously watching the horizon for signs of the German cruisers that had recently been spotted in Mexican waters. On August 5th, it seemed as if their wait was over. That morning, a patrol boat rushed into Victoria Harbour bearing a terrifying message: two mysterious ships were approaching the city! Fearing a German attack, the batteries readied for combat. As the unknown vessels neared the harbour, it became clear that they were submarines – and friendly ones at that. CC1 and CC2, as they came to be called, were to be the newest additions to the Pacific fleet of the Royal Canadian Navy. The purchase had been sudden and very secretive, and Premier Richard McBride had completely forgotten to tell the militia about his plans.[7]

The Quarter Guard presents arms while on duty at Macaulay Point. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

Asides from this embarrassing incident, the gunners of Victoria had a fairly unexciting war ahead of them. Many enlisted for overseas service, replaced at the batteries by civilian volunteers. Others ended up at Willows Camp, instructing new recruits. British Columbians spent the next four years dreading a seaborne attack that never came, understandably terrified by news of the havoc wrought by German battleships and U-boats in the Atlantic. Although Victoria’s coastal defences were never battle-tested, they nonetheless helped to prepare hundreds of local men for overseas service – including a certain struggling real estate salesman, who would soon rise to command the entire Canadian Corps.

By Kirsten Hurworth

Notes

[1] Ronald Lovatt, “A History of the Militia Gunners of Victoria to 1956,” BA Thesis, University of Victoria, 1974, 14-15.

[2]Lovatt, “A History of the Militia Gunners of Victoria to 1956,” and F.A. Robertson, 5th (B.C.) Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery and Early Defences of the B.C. Coast: Historical Records (1925), 103. In the possession of the 5th (B.C.) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery Museum.

[3] Victoria Times, May 12, 1906, quoted in F.A. Robertson, 5th (B.C.) Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery and Early Defences of the B.C. Coast: Historical Records (1925), 103-105. In the possession of the 5th (B.C.) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery Museum.

[4]Robertson, 5th (B.C.) Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery and Early Defences of the B.C. Coast: Historical Records, 92, and Lovatt, “A History of the Militia Gunners of Victoria to 1956,” 45.

[/acp]

[5] “Coast Defences – 1893-1906,” Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

[6]“Coast Defences – 1906-1936,” Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

[7] Starr J. Sinton, “CC1 and CC2 – British Columbia’s Submarine Fleet,” CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum.