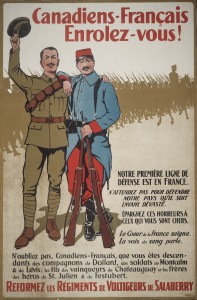

Au déclenchement de la guerre, le Canada avait peu de difficulté à attirer un nombre suffisant de recrues pour maintenir l’armée sur le terrain. L’enthousiasme populaire pour une guerre qui devait être courte et glorieuse, un taux de chômage élevé ainsi qu’un surplus de jeunes hommes célibataires avaient contribué à créer un environnement propice au recrutement. De plus, les salaires offerts par l’armée étaient attirants dans une économie en perte de vitesse. Cependant, le recrutement était beaucoup moins efficace chez les Canadiens français en grande partie à cause de l’approche très maladroite de Sam Hughes [ministre de la Milice] qui, depuis longtemps, attisait les sentiments antifrancophones et anticatholiques pour se faire du capital politique.[1] Par contre, l’opposition à la conscription ne voulait pas dire l’opposition à la guerre. En février 1917, la campagne du Fonds patriotique canadien qui demandait de faire un don équivalent à une journée de salaire obtient un grand succès au Québec. Dans un esprit de bonne entente, Le Devoir et La Presse offrent gratuitement de l’espace à la campagne. Près des deux tiers des donateurs au fonds sont des Canadiens français.

Parallèlement, il est de plus en plus évident que les volontaires ne suffisent plus à répondre à la demande de renforts pour le Corps canadien. En avril, le recrutement tombe à 5530, puis connaît une légère augmentation en mai après la victoire de Vimy. Pourtant, dans cette seule bataille, presque le double de soldats avaient été tués ou blessés. Après une visite aux troupes stationnées en France, Borden, qui s’était déplacé en Grande-Bretagne avec les autres chefs des pays du Commonwealth, revient convaincu que la conscription représente la seule solution.

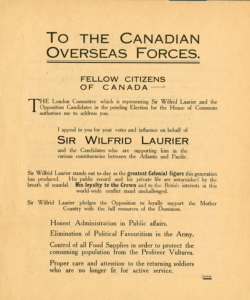

Cherchant à soutenir les efforts de conscription, Borden tend la main à l’opposition afin de former un gouvernement de coalition. Laurier refuse, ayant peur de perdre sa base politique au profit d’Henri Bourassa, la figure de proue contre la guerre au Québec. Le Parti libéral est divisé sur la question et plusieurs députés libéraux acceptent de se joindre à la coalition unioniste. En juin, le gouvernement unioniste présente un projet de loi qui aurait permis au gouvernement d’enrôler tous les hommes entre 18 et 60ans.

L’opposition à la conscription ne se limite pas au Québec. Plusieurs fermiers sont opposés à cette mesure, soutenant qu’ils ont besoin de leurs fils à la maison afin de répondre à l’augmentation de la demande pour les produits agricoles. Les chefs syndicaux quant à eux appuient la «conscription de la richesse», soutenant que le fardeau du service doit être partagé autant par les riches que par la classe ouvrière. D’autres s’opposent à la guerre par conscience ou parce qu’ils considèrent cette loi comme une attaque à la démocratie canadienne. Les minorités visibles, à qui on refuse l’égalité politique, s’opposent au fait d’être appelés à servir un pays qui refuse de leur accorder les mêmes droits qu’aux autres citoyens.[2] Au Québec, cependant, la réaction est vive et frappante.

Alors que la loi sur la conscription prend forme sous le gouvernement unioniste, Borden doit faire des compromis. Il promet alors des exemptions aux fermiers, à leurs fils et aux objecteurs de conscience. La tranche d’âge de ceux qui sont éligibles est également réduite. À la fin août, la Loi du service militaire est votée. Tous les citoyens mâles entre 20 et 45ans sont désormais soumis au service militaire pour la durée de la guerre.

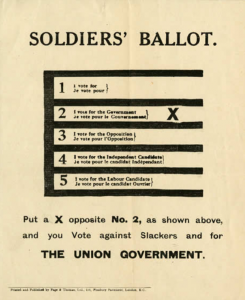

Pour augmenter son soutien aux élections qui s’annoncent imminentes, Borden introduit deux changements majeurs aux lois électorales: la Loi des électeurs militaires et la Loi des élections en temps de guerre.

La Loi des électeurs militaires

La Loi des électeurs militaires définit comme électeur militaire tout membre actif ou retraité des Forces armées canadiennes incluant pour la première fois les femmes, les Indiens et les personnes âgées de moins de 21ans. Elle permet aux électeurs militaires d’attribuer leur vote à n’importe quelle circonscription où ils résident normalement.

L’élément le plus choquant de cette loi se retrouve dans une clause qui retarde le dépouillement des votes militaires jusqu’à 31jours après la tenue de l’élection. Lorsqu’aucune circonscription n’est indiquée sur le bulletin de vote, le parti choisi par l’électeur peut attribuer le vote à la circonscription qui en a le plus besoin. Ainsi, les votes militaires peuvent être utilisés pour changer les résultats dans les circonscriptions où la marge de victoire est étroite.

La Loi des élections en temps de guerre

La seconde loi a le double objectif d’augmenter le nombre d’électeurs qui appuient la conscription et de réduire le nombre de ceux qui s’y opposent. Ainsi, l’épouse, la veuve, la mère, les sœurs et les filles de quiconque sert ou a servi reçoivent le droit de vote à la condition de satisfaire aux exigences en matière d’âge, de nationalité et de résidence. Par ailleurs, la Loi refuse le vote aux objecteurs de conscience, à ceux qui sont nés dans un pays ennemi et qui ont été naturalisés après 1902 ou à quiconque est reconnu coupable d’une faute en vertu de la Loi du service militaire.

Le débat historique

Le débat historique autour de l’élection de 1917 porte sur deux questions fondamentales: L’opposition à la conscription était-elle un enjeu essentiellement canadien-français? La conscription était-elle nécessaire?

L’opposition à la conscription était-elle un enjeu essentiellement canadien-français?

L’historien Desmond Morton y répond comme suit:

«De nombreux Canadiens avaient décidé de résister à la conscription, mais c’est la résistance canadienne-française, mise de l’avant par Henri Bourassa et son journal Le Devoir, qui a rapidement été récupérée par plusieurs Canadiens d’origine britannique pour expliquer toute pénurie d’effectifs militaires. La majorité des Canadiens ignorait ou considérait sans importance les ratés de la milice canadienne, une institution entièrement unilingue anglophone. L’étaient aussi les arguments voulant que les Québécois soient mieux employés à cultiver ou à fabriquer des bombes dans les nouvelles usines montréalaises de munitions.»

À l’époque, c’était presque un cliché d’affirmer que l’opposition à la conscription était un enjeu canadien-français. Le climat surchauffé de la campagne électorale ne faisait que jeter de l’huile sur le feu. Laurier était dénoncé comme un traitre et ses partisans traités de lâches. Soutenir le gouvernement unioniste était un vote contre les fainéants. Par contraste, les libéraux de Laurier soutenaient qu’un vote pour Laurier était un vote pour un gouvernement honnête, un rejet du favoritisme politique dans l’armée et une promesse de bons traitements pour les vétérans. Malgré son soutien de longue date envers la conscription, la presse protestante condamnait une telle intolérance et avait lancé un appel au dialogue et à la compréhension.

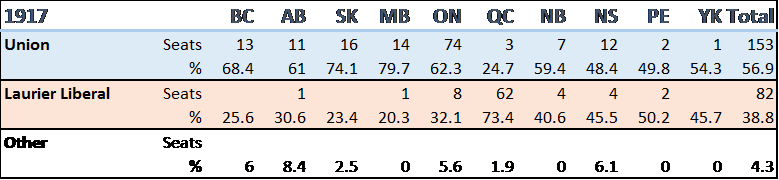

L’écrasante majorité unioniste de 153 contre 82 tend à voiler un changement beaucoup moins marqué, soit que le vote populaire n’a bougé que de 10% à l’échelle nationale. En plus d’obtenir une vaste majorité au Québec, les libéraux de Laurier obtiennent un soutien important dans les Maritimes. En Ontario, le gouvernement unioniste n’obtient que trois sièges de plus qu’en 1911. Si on porte un œil critique aux résultats, il faut noter que l’utilisation judicieuse du vote militaire pourrait avoir fait changer la décision en faveur du gouvernement dans au moins 14circonscriptions.

La conscription était-elle nécessaire?

Il ne fait aucun doute qu’au moment où la conscription est entrée en vigueur, la perspective d’une victoire des Alliés était loin d’être évidente. La Russie s’était effondrée et les troupes américaines n’étaient pas encore arrivées en grand nombre. Il y avait encore de durs combats à gagner et personne n’aurait pu prédire la fin de la guerre en novembre 1918. Si la guerre s’était poursuivie en 1919, le petit nombre de conscrits, considéré par plusieurs comme insignifiant, serait devenu essentiel pour le maintien du Corps canadien.

Les chiffres sont irréfutables. Seulement 47509conscrits servaient outre-mer et pas plus de la moitié d’entre eux étaient au front.[6] Parmi ces derniers, la plupart auraient été assignés à des unités d’infanterie où la demande était la plus grande. Dans ces bataillons d’infanterie, les nouveaux arrivés auraient été assignés à des compagnies de fusiliers de première ligne. Dans le Corps canadien, ces compagnies ne comptaient qu’environ 10000hommes ou moins de la moitié du nombre total du Corps.

Ce que ces chiffres n’illustrent pas est l’impact de la conscription sur le nombre de volontaires. Plusieurs hommes ont dû choisir entre attendre d’être conscrits tout en sachant qu’ils subiraient l’opprobre public ou s’enrôler volontairement et être vus comme des héros. On pourrait avancer l’hypothèse que la moitié de ces hommes ont été «encouragés» à s’enrôler tard dans la guerre par la probabilité d’être bientôt conscrits.

Si on considère tous ces facteurs, il n’est pas déraisonnable d’assumer que vers la fin de la guerre, de 10 à 20% des troupes de première ligne étaient composées de conscrits ou de volontaires motivés par la menace de la conscription.

[1] See Tim Cook, The Madman and the Butcher: The sensational wars of Sam Hughes and General Arthur Currie, Penguin Books, Toronto 2010.

[2] James W. St. G. Walker, “Race and Recruitment in World War 1: Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force” in Canadian Historical Review, LXX, 1, 1989 https://web.viu.ca/davies/H355H.Cda.WWI/Race%20and%20Recruitment%20in%20World%20War%20One.pdf

[3] Desmond Morton, Fight or Pay: Soldier’s Families in the Great War, UBC Press, Vancouver, 2004.

[4] See Gordon L. Heath, “The Protestant Denominational Press and the Conscription Crisis in Canada 1917-1918” in CCHA Historical Studies, 78 (2012), 27-46.

[5] https://www.elections.ca/

[6] Col G.E.L Nicholson, The Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919: Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War, Queen’s Printer, Ottawa. 1962, 551.