Learn more about the navy in the digital archive

“A Navy of Her Own”: The Birth of the Naval Service

On the 7th of November, 1910, a lone cruiser steamed into Esquimalt Harbour. Aged but exuberant, HMCS Rainbow greeted the waiting crowd with a twenty-one gun salute and eased into port. Victoria was now the proud home of the Pacific fleet of the Naval Service of Canada, such as it was.

The Dominion had attempted to establish a proper navy before. By 1904, Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government, prodded by Robert Borden’s Conservatives and concerned citizens, had acquired eight small vessels to defend the nation’s fisheries. Although Laurier and his supporters liked to think of these ships as “the nucleus of a Navy,”[1] these vessels were not at all prepared to protect the country from a genuine naval threat. That year, the British Admiralty declared that the imperial ships and garrisons stationed at Halifax and Esquimalt were to be withdrawn. Laurier’s government responded by volunteering to take command of the forts, and the British accepted. Still, no decisive steps were taken towards the creation of a professional Canadian navy, and the Liberals delayed the transfer of the naval bases, uncomfortable with the financial commitment that the forts represented.[2] The future of the Dominion’s naval defences was a very contentious topic, and no politician was willing to risk losing support by raising the issue. Nationalistic citizens insisted that Canada’s money ought to be spent at home, encouraging Canadian industry and producing a navy that would suit the Dominion’s needs. Some imperialists also desired the creation of a Canadian navy, thinking that those ships could aid the British Royal Navy in times of crisis. Other imperialistic English Canadians felt that Canada had no need of its own naval force, and should focus its resources on providing financial support to the Royal Navy. French Canadians, on the other hand, railed loudly against any policy that threatened to increase the Dominion’s obligations to Great Britain. Canada’s “naval question” prompted fierce arguments throughout the Dominion, exacerbating imperialist-nationalist tension and deepening the divisions between French Canadians and English Canadians. In Victoria, one of the loudest voices in the debate was that of the local branch of the Navy League of Canada, which was staunchly imperialist. Their views were neatly articulated by Clive Phillipps-Wolley, a British-born Victorian and author who declared that it was

“the duty… of every patriotic Canadian independent of party, to press in every way for a substantial contribution to that Imperial Navy, upon which the very existence of Canada as a portion of the Empire depends.”[3]

The issue became more urgent than ever before on March 16, 1909, when the British Admiralty turned to the Empire for help in maintaining its mastery of the world’s seas. Four years earlier, the Royal Navy had sparked a naval arms race by launching the HMS Dreadnought, a battleship that vastly outclassed every other warship afloat. Now it looked like Germany’s fleet of “dreadnoughts” might match and exceed Great Britain’s as soon as 1912. Shocked by this news, the Liberals and the Conservatives began negotiating with each other and the British Admiralty. Out of these talks emerged the Naval Service Bill, which Wilfrid Laurier presented to the House of Commons on January 12, 1910. The Naval Service of Canada was born on May 4, 1910, when King George V gave his royal assent.

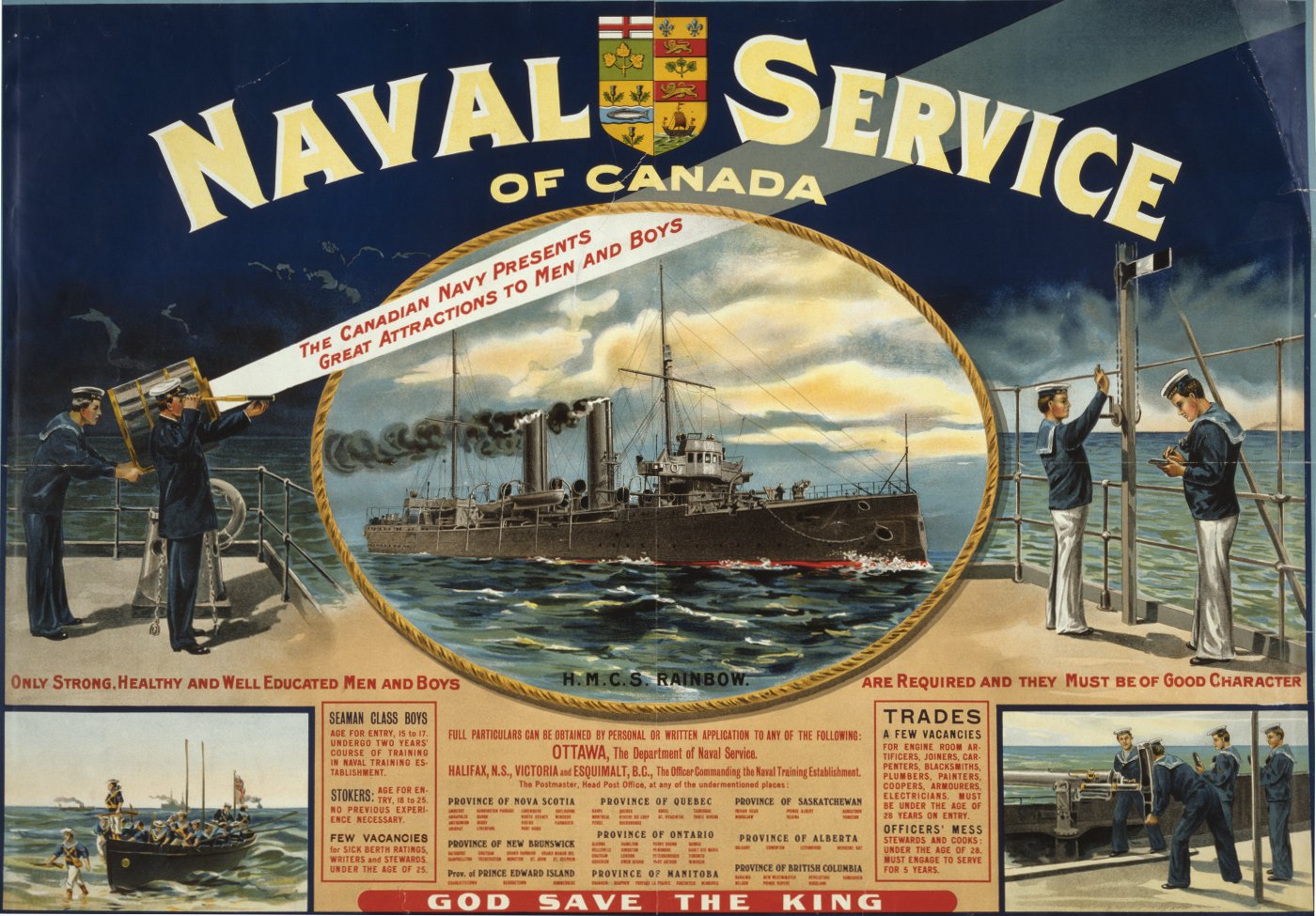

A recruiting poster for the Naval Service of Canada, featuring HMCS Rainbow. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

That November, HMCS Rainbow reached Esquimalt with a crew of British sailors and officers, on loan from the Admiralty. Two days later, the Dominion finally took possession of the old British naval bases at Esquimalt and Halifax, as had been agreed five years earlier. Now, Canada had a navy, and the naval fortifications of Esquimalt were officially the property and responsibility of the Dominion of Canada. Victorian journalists captured the city’s pride and excitement at becoming the Pacific base for the nation’s new navy, writing of the Rainbow’s arrival as “a promise of things to come.”[4] The Victoria Times insisted that the Naval Service would grow to be a mighty force, one which would “add dignity to our name and prestige to our actions”[5] the Dominion was maturing, taking on “new burdens” and sailing into “the ocean of the future.”[6] Unfortunately, rough waters lay ahead for both Wilfrid Laurier and the Naval Service.

“Heartbreaking Starvation Time”: The RCN, 1911-1914

Many Canadians were dissatisfied with the “tin-pot navy” that Wilfrid Laurier had created. Imperialists despised the Naval Service Act, seeing it as a woefully inadequate measure that threatened the cherished tie between the Dominion and Great Britain. Meanwhile, French-Canadians and ardent nationalists found Laurier’s policy upsettingly imperialistic. Losing support and facing aggressive criticism, the Liberals quietly stepped away from the nation’s fledgling navy.

HMCS Rainbow sails by the McLoughlin Point Fog Alarm Building, Esquimalt. Courtesy of Craig Cotter at the Museum of the 5th (BC) Regiment Royal Canadian Artillery.

Although the Naval Service did acquire a new name – the Royal Canadian Navy, given royal assent in August, 1911 – the bigger, better ships that had been planned did not arrive. The RCN’s prospects did not improve when Robert Borden and the Conservatives ousted Laurier’s Liberals from power, and the naval question did not become any less controversial. Before becoming Prime Minister, Borden had argued that the best way for the Dominion to support the Royal Navy was through a significant financial contribution to Great Britain’s dreadnought-building program. By the time that Parliament opened in 1912, he no longer felt that this was necessary – but Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the British Admiralty, disagreed.[7]

Commander Walter Hose stands on the deck of his ship, HMCS Rainbow. Courtesy of the Canadian War Museum.

During his next visit to London, Borden was informed that Germany had recently made frightening advances in the race for naval arms. When the Prime Minister returned home, he announced that Canada would give the Royal Navy $35 million, enough money to build not just one, but three dreadnoughts.[8] Once again, the “naval question” prompted fiery debate across the nation. In Parliament, the argument over Borden’s Naval Aid Bill became so fierce that the Conservatives were moved to invoke closure. This was the first time in Canadian history that this step was taken.[9] While Liberals, Conservatives, and naval enthusiasts argued furiously over

Borden’s proposal, the RCN literally struggled to stay afloat. Since coming to power, the Conservative government had halved the funds meant to support the navy, and shown little interest in recruiting new volunteers or disciplining deserters. In Victoria, Commander Walter Hose of HMCS Rainbow could only watch as his ship and the navy she belonged to entered a “heartbreaking starvation time,” desperate for men and money.[10]

Yet Hose was not ready to give up. The Rainbow’s captain began to ponder the creation of a voluntary “citizen navy,” and proposed this to his Director, Rear-Admiral Sir Charles Kingsmil; the Director, “very depressed and much afraid” at the thought of what Borden’s government had in store for the navy, insisted that such a thing was impossible.[11] The Minister of the Naval Service, Douglas Hazen, was more helpful. With Hazen’s permission, Hose began to train an unofficial naval reserve unit. Fortunately, Hose and his sailors attracted the attention of both the Governor General and Premier Richard McBride. These esteemed supporters helped to convince Prime Minister Borden to create the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve, established on May 14, 1914.[12] Soon after this, Hose was told to take the Rainbow to the Bering Sea to support a sealing ban that was in Canada’s interests. These plans were changed on July 20, when the Rainbow was ordered to sail to Vancouver instead.

There, hundreds of Sikh men, women, and children waited aboard the Komagata Maru, insisting that they be allowed to enter the country and protesting the exclusionist immigration policies in place. With the guns of the Rainbow upon them, they had little choice but to leave, departing on 23 July, 1914.[13] Six days later, the Rainbow received another order – the Dominion was to prepare itself for war. The sailors of Victoria would spend the next few years engaging in missions monotonous and clandestine, bravely serving in their nation’s tiny “tin-pot navy.”

HMCS Rainbow (left) and the SS Komagata Maru in Vancouver Harbor. Courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

By Kirsten Hurworth

Notes

[1] L.P. Brodeur, “Proceedings of the 1909 Imperial Conference on Naval and Military Defence,” Fourth day, 5 August 1909,” in L.P. Brodeur Papers, Public Archives of Canada, 43, quoted in Nigel D. Brodeur, “L.P. Brodeur and the Origins of the Royal Canadian Navy,” in The RCN in Retrospect, 1910-1968, ed. James A. Boutilier (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1982), 14.

[2] Barry M. Gough, “The Royal Navy’s Legacy to the Royal Canadian Navy in the Pacific, 1880-1914,” in The RCN in Retrospect, 1910-1968, ed. James A. Boutilier (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1982), 9.

[3] L.P. Brodeur, “An Address Delivered by Clive Phillipps-Wolley on Behalf of the Victoria-Esquimalt Branch of the Navy League to an Audience in the City Hall, Victoria, British Columbia, Tuesday 14 May 1907,” in L.P. Brodeur Papers, Public Archives of Canada, quoted in Nigel D. Brodeur, “L.P. Brodeur and the Origins of the Royal Canadian Navy,” in The RCN in Retrospect, 1910-1968, ed. James A. Boutilier (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1982), 19.

[4] Victoria Times, 7 November 1910, quoted in Barry M. Gough, “The Royal Navy’s Legacy to the Royal Canadian Navy in the Pacific, 1880-1914,” in The RCN in Retrospect, 1910-1968, ed. James A. Boutilier (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1982), 3.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Victoria Colonist, 8 November 1910, quoted in Barry M. Gough, “The Royal Navy’s Legacy to the Royal Canadian Navy in the Pacific, 1880-1914,” in The RCN in Retrospect, 1910-1968, ed. James A. Boutilier (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1982), 3.

[7] Roger Sarty, “Toward a Canadian Naval Service, 1867-1914,” in The Naval Service of Canada, 1910-2010 – The Centennial Story, ed. Richard H. Gimblett (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2009), 16.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Roger Sarty, “Naval Aid Bill,” The Canadian Encyclopedia.

[10] Sarty, “Toward a Canadian Naval Service, 1867-1914,” in The Naval Service of Canada, 1910-2010 – The Centennial Story, 17.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Wilf Lund, “Rear Admiral Walter Hose: Saving the RCN,” CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum

[13] “The Incident,” Komagata Maru, Continuing the Journey, Simon Fraser University Library.

Local Museums and Historic Sites

CFB Esquimalt Naval and Military Museum