The Canadian Corps

(The standard NATO symbols used for simplicity in these diagrams were not used during the First World War. Diagrams have been adapted from various sources.)

Following the bloody fighting of 1915-1916, the resolve to group all Canadian combat troops in a Canadian Corps came to fruition. Although the Corps was initially commanded Byng, a British regular officer and had numerous British officers in key staff positions, the intent to shift toward Canadians was relentless. After Vimy Ridge in April 1917, command passed to Arthur Currie who in 1914 had been a Victoria real estate dealer and a Lieutenant Colonel in the militia.

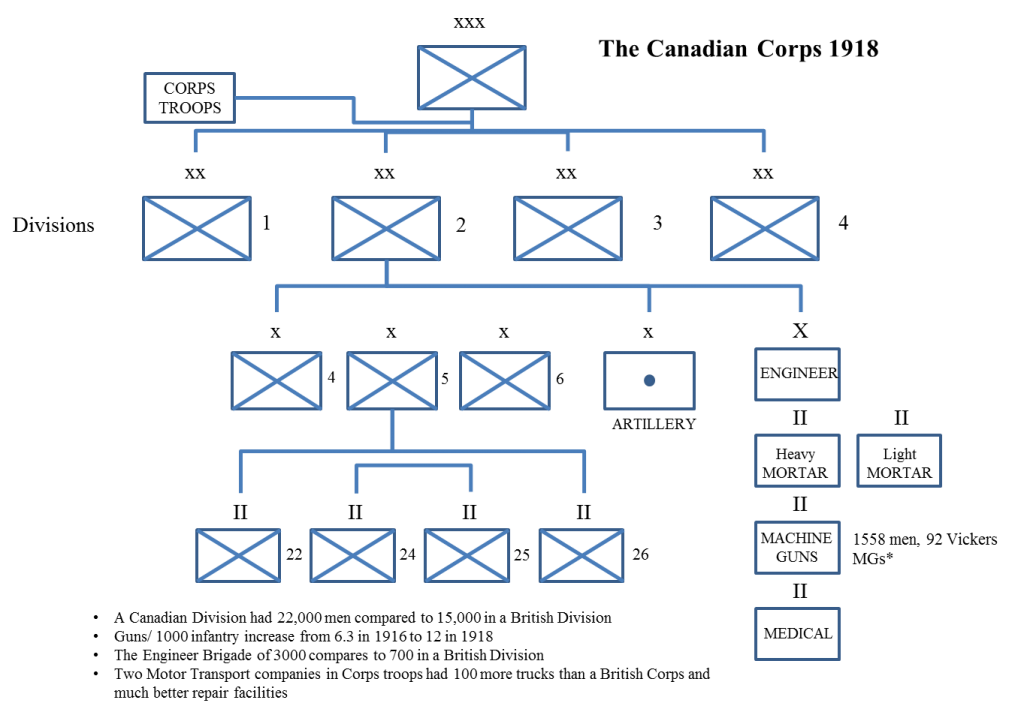

There was also a dramatic increase in the support available from within the Division and the Canadian Corps. Within the British army both the Division and Corps we formations that changed depending on the operational task at hand. The number of brigades in a division and divisions in a Corp could change depending on operational requirements. In the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), however, from the formation of the corps in 1916, both divisions and the corps itself remained stable. Currie resisted pressure to create a fifth division on 1917 in favour of keeping the existing formations and units up to strength.

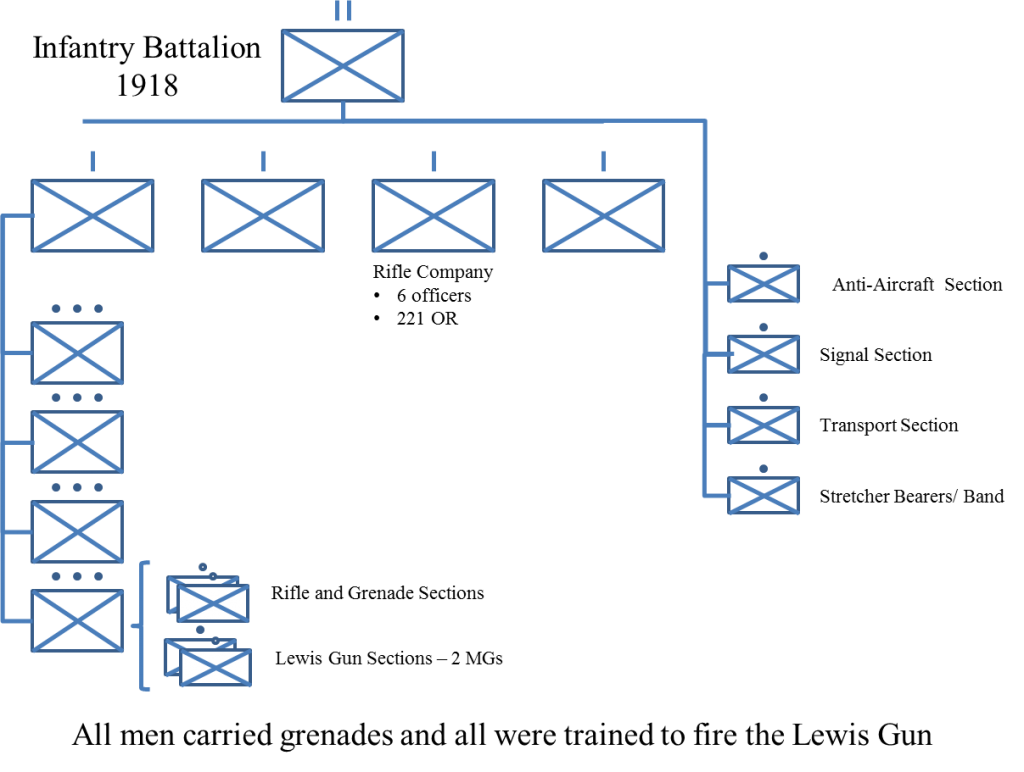

At the sharp end, the most significant change was the dramatic increase in combat power. The experience of Ypres in 1915 and the Somme battles of the fall of 1916 had brought home the need for increased firepower and greater mobility in the infantry battalion. With the adoption of the light Lewis gun, infantry battalions had dramatically increased the number of machine guns available. Now there were two machine guns in each platoon capable of providing suppressive fire during the attack. In addition, the Division now included a machine gun battalion equipped with 92 Vickers machine guns to provide close support in the attack and to strengthen the defence with arcs of interlocking fire. The Canadian Division was almost 50% larger than a British Division. It included an Engineer Brigade of 3,000 men compared to only 700 in a British Division. The number of guns per thousand infantry had grown from 6.3 in early 1916 to 12 by the end of the war.

The light Stokes Mortars and Vickers Machine Guns in the Division could be massed when needed but were closely affiliated with the brigades. It was typical for infantry units to “second” senior NCOs and officers to these immediate support units. The number of guns and their ability to concentrate fire and work closely with the infantry had also dramatically increased.

The Infantry Battalion

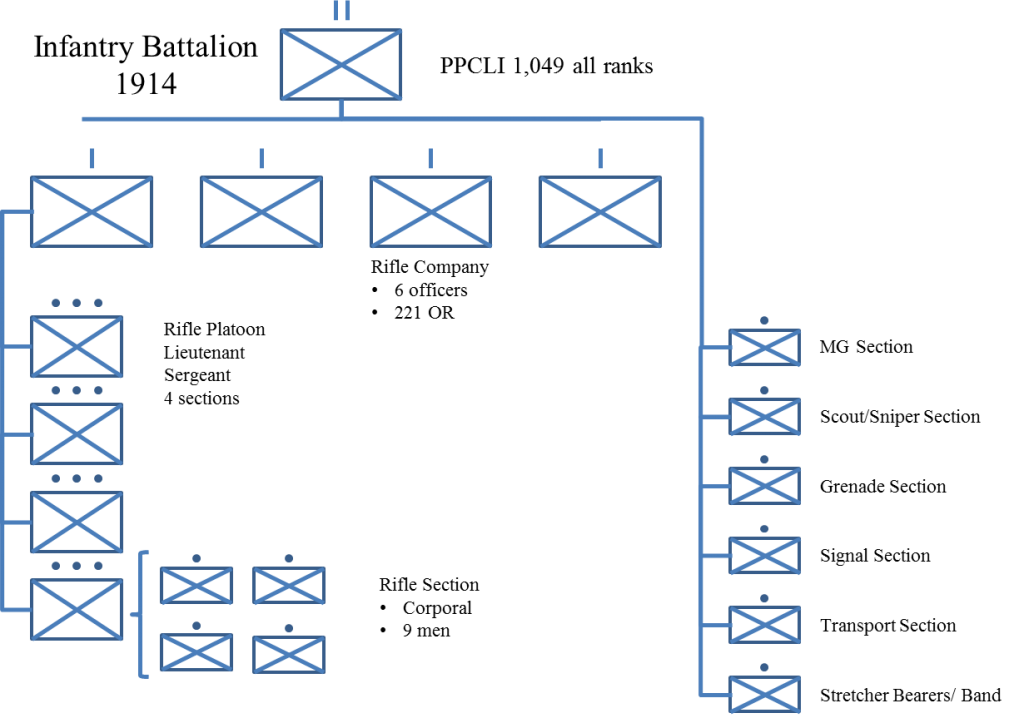

At the outbreak of war the structure of the infantry battalion was in a state of flux. In Canada, the Royal Canadian Regiment was organized with eight companies, a structure well suited to its role in training the Militia. In Britain, the shift had recently been made to battalions of four companies. This was the model immediately adopted by the PPCLI and later the rest of the CEF. The battalion of 1914 initially had only two Vickers Machine Guns. Although this soon increased to four, they were unwieldy weapons that were difficult to move forward in an attack. In addition to suffering an overall deficiency in artillery support compared to the opposing Germans, the battalion had no immediate support from mortars. Even grenades were in short supply in the early days of 1915. The individual soldier was ill-equipped. Steel helmets were not available in 1915 at Ypres, nor were gas masks. Instructions at the time were for soldiers to breathe through a dampened piece of gauze.

By the end of the war, the battalion had dramatically increased firepower. In addition to an anti-aircraft machine gun section, every platoon now had two Lewis Guns that could accompany troops in the attack. Stokes Mortars provided dedicated indirect fire support under command of the battalion. Steel helmets and gas masks had also been added to the general kit of every soldier and all were trained to use both grenades and fire the Lewis Gun.

The Problem with Regiments

Students of the Great War are often puzzled by the shifting use of the term regiment. In armies patterned after the British Army, the infantry regiment is not an operational unit. Rather it identifies a group of soldiers who have distinctive dress, badges, customs and traditions. The Regiment will typically have responsibility for recruiting, training and personnel management. Often the Regiment will have responsibility for a “home station” of Regimental Depot. In the normal pattern, each regiment will have several associated infantry battalions. In operations these battalions are assigned to brigades or divisions depending on operational need. Thus in the Royal Scots, a regiment had three battalions. The first battalion served in the 81st Brigade and the second battalion in the 8th Brigade in a different division. The third battalion remained in reserve in the UK throughout the war.

For the pre-war Canadian militia however, virtually all Regiments were limited to a single battalion. With mobilization even these links disappeared for most. For example, the Gordon Highlanders of Victoria was a regiment that raised and trained troops in Canada but when they were ready for deployment, the links to the parent regiment were largely severed. In the initial wave of troops, soldiers from several militia regiments including the Gordon Highlanders were grouped together to form the 16th Battalion.

In the infantry, only the Royal Canadian Regiment and Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry retained their original regimental designation on deployment. To support the ongoing needs for reinforcement, recruiting and training “regiments” in Canada were linked to units of the CEF. For example, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was grouped with the Eastern Ontario Regiment for reinforcements. It was the reality on the ground however that ultimately dictated how reinforcements flowed to battalions at the front. For example, in the last half of 1916, a large draft from the 13th Canadian Mounted Rifles from Montreal reinforced the Patricia’s. In September 1916, a platoon of Japanese Canadians from the Calgary area, formed part of a draft from the 52nd Battalion which was at least nominally part of the Royal New Brunswick Regiment.

Other Regiments

To confuse matters still further, the term regiment today is also applied to Armoured, Artillery and Engineer operational units in the same way that the term battalion is used for the infantry. During the First World War however, the Artillery batteries were groups in artillery brigades. For example in 1918, the artillery of the Third Canadian Division included:

the 9th Brigade, Canadian Field Artillery (CFA)

- 31st Field Battery

- 33rd Field Battery

- 45th Field Battery

- 36th Howitzer Battery

the 10th Brigade, C.F.A.

- 38th Field Battery

- 39th Field Battery

- 40th Field Battery

- 35th Howitzer Battery

3rd Division Ammunition Column

The term Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery was not approved until 1935.