Religion in Victoria

Click hereto view documents in the digital archive

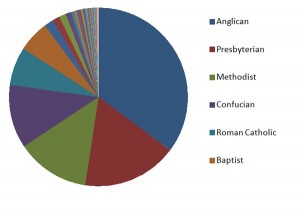

For many, religious observance was tied to heritage. Scotsmen abounded in the Presbyterian churches, British ex-pats in the Anglican and Methodist churches. Victoria was the seat of the Anglican Diocese of British Columbia but also had high level Catholic leadership and other large congregations. The British influence in Victoria is evident in twice as many people listing Anglican (9,563) than the next highest religion (Presbyterian, 4,674) in the 1911 Census.[1]

Religions in Victoria in 1911. Source data taken from viHistory

The long-standing Jewish synagogue, Chinese religious communities, and Hindu temples provided services for non-Christian congregants. While religious centres provided social activities and a like-minded community, they also acted as a social service provider and supporter of military forces and families.

As the seat of the Bishop, Christ Church Cathedral was well represented in the Anglican life of Victoria. Christ Church became the hub for Victoria’s Anglican war effort during and after the war as various committees worked to support the city and its troops. The War Service Commission attempted to “[keep] the Church alive in its service of soldiers, sailors, airmen, chaplains and nurses” beginning in January 1919, by encouraging service members to return to their religious communities after the war.[2]

Oversees, the Anglican Diocese of BC contributed to the war effort in two major ways: by sending chaplains to serve with and minister to the troops, and by sponsoring the volunteer service organization known as the Church Army. 11 clergymen from the BC diocese served with Canadian troops overseas, a significant amount given only 12 Anglican churches were active south of the Malahat in 1914.[3] One chaplain of note was St. Mary the Virgin’s Rev. George H. Andrews who served with the CEF from 1916-1918. Andrews had already served 25 years as chaplain in the Imperial Services and saw no problem stepping back into military life at age 56.[4] His battalion, the 88th Regiment Victoria Fusiliers, donated the King’s and the Regimental Colours to St. Mary’s church on 14 November 1920 in honour of their chaplain’s service.[5] When Rev. Andrews returned to Oak Bay in late 1918 he is said to have “lost none of his enthusiasm for his work.”[6]

The Church Army was an organization that rarely received journalistic attention like the similar YMCA or Salvation Army. The Church Army provided recreation, medical care, food, re-training, social activities, etc., for men and women serving in at least 10 countries or regions. Many Victoria congregations heard stories from their own clergy who had volunteered with the Church Army for short periods of time. In March 1917 the Church Army lost a great deal of supplies as the Allies beat a retreat across much of the Western Front causing a push for renewed fundraising.[7]

Places of worship like First Baptist, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian and St. Mary’s saw many parishioners leave during the War. This sudden absence did not seem to limit the churches (congregational giving was down because of the pre-war depression anyways) but meant that the churches were responsible for more direct care of the families of those serving and the men who came home as veterans. A 1918 open letter by Rev. Ernest G. Miller published in the Colonist begged Victorian’s to donate generously to support William G. Wallace, a wounded soldier whose Victoria house had burned down six weeks prior.[8] Other congregations supported families financially or with legal matters while the husbands were overseas.

After the War, churches built memorials and hung plaques to highlight their veterans. Among the plaques and honour rolls hung on church walls today include some other more functional memorials. Some returning soldiers, like those at St. John’s church in Victoria, were put to work in the restoration and enlargement of church buildings. By April 1920, the returned soldiers of St. John’s had built magnificent oak reredos (the decorative wood panel behind the altar) through the Red Cross workshop on Johnson Street. The parishioners had donated generously for the new reredos, a memorial to the war, and the spirit of giving increased in the years following the Armistice.[9]

Most Christian communities cooperated during the war on larger faith issues such as the Day of Intercession (prayer) for military personnel in 1915 as requested by the King, or the 1917 religious summer school, a non-denominational school “for the purpose of mutual study on definite lines.”[10] These church organizations followed national guidance in supporting the war and the Canadian government. Religious differences did come to the fore with the growth of newer religious organizations such as the pacifist Quakers or the Church of Christian Science. The Diocesan Gazette featured articles in 1917 about how to “cure” the attack by Christian Science.[11]

By Ben Fast

[1] “viHistory Census Search, 1901-1911 religion comparison,” viHistory, https://vihistory.ca/search/searchcensusreligion.php?start=0&show=n (accessed 17 July 2013).

[2] Anglican Diocese of British Columbia Archives (herafter ANGBC), Diocesan Gazette, vol. 8, no. 8 (January 1919), 4.

[3] ANGBC, Diocesan Gazette, vol. 8, no. 6 (November 1918), 5.

[4] “George Hubert Andrew attestation papers,” Library and Archives Canada, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 179 – 49, https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/databases/cef/001042-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=10139&PHPSESSID=bh9bahiausf0rfd94l7gh2t3o7 (accessed 7 July 2013).

[5] ANGBC, 88th Regiment Victoria Fusiliers at St. Mary’s Anglican Church 1920, file 92.45, Photo 218, 1920.

[6] St. Mary’s church history, 8.

[7] ANGBC, Diocesan Gazette, vol. 8, no. 7 (December 1918), 9-10.

[8] “A Deserving Case,” British Colonist, 1918, no page.

[9] Stuart Underhill, The Iron Church (Victoria: Braemar Books Ltd., 1984), 51.

[10] “Church is Holding a Summer School,” Victoria Daily Times, 9 July 1917, 15.

[11] ANGBC, Diocesan Gazette, Vol 6, No. 12, May 1917, 1-2.