Germans in Victoria

Before the First World War, Victorians largely accepted the local German population into the middle and upper class of the city. German immigrants and those of German descent were prominent business owners and political figures.[1] German residents participated in German Clubs that perpetuated German language skills and German cultural identity. These clubs did not threaten the image of Anglo-Saxon settlers; rather, they emphasized the similarities between Germans and British.[2]

When conflict in Europe started, Victorians began to re-examine the place of Germans within Victorian society. Because Germany became an enemy of Britain, Victorians increasingly viewed Germans with hostility. Tensions came to a head on 8 May 1915 after the sinking of the

Spectators during the Anti-German Riot, 08 May 1915. Permission to use this image must be obtained from the BC Archives. Image Courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives – Call Number: A-02709

See BC Archives

RMS Lusitania by a German U-boat. What has become known as the Anti-German Riot of 1915 began when a group of soldiers stationed at the Willow’s training camp started breaking windows and mirrors at the German-owned Kaiserhof Hotel. The Kaiserhof was targeted because the soldiers thought that Victorian Germans had congregated at the hotel bar to celebrate the sinking of the Lusitania. The small group of soldiers grew into a large mob that looted a number of German-owned businesses in downtown Victoria until they were dispersed by the police, fire department, and military. Further violence continued the following evening when looters once again targeted German businesses culminating in the reading of the Riot Act.[3]

The Anti-German Riot highlighted shifting attitudes towards Germans. During this period, Victorians began to focus on the differences, rather than the similarities, between the ideal image of British Victorians and Victoria’s German population. In the months following the riot, the city began alienating Germans, causing some to leave for more neutral cities like Seattle. Others were interned in the province’s interior where they were held for the duration of the war. Internment was a federal initiative started in 1914 signaling a distinct shift in attitudes towards Germans in Canada.[4] Germans, however, were still seen as different from other racially defined groups. For example, German prisoners were often able to take part in programs like book clubs and distance-education programs that were not provided for Austro-Hungarian or other racially defined internees.[5]

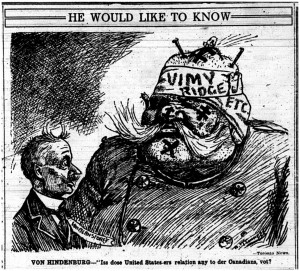

Cartoon depicting the German Kiaser after the battle of Vimy Ridge. Victoria Daily Times 07 May 1917, Page 03.

During the First World War, being racially identified as “white” had less to do with skin colour than with public perceptions of what it meant to be culturally white.[6] Our understanding of what it means to be white has changed; though we may now think of both Germans and British as white, in 1915, being a German in Victoria was very different from being British in Victoria. Before the war, similarities were emphasized, whereas afterwards differences were highlighted. The shifting ideas in Victoria surrounding “whiteness” demonstrate how ideas about race are shaped by culture and place. Scholars that study race look at the ways that race is socially constructed. Race is not a biological trait but a framework by which people understand how they are different from one another; however, perceptions of race is complicated by the assumption that racial characteristics are biologically determined. The soldiers who started the Anti-German Riot believed that Germans were biologically predisposed to be traitors to the Crown.

By Ashley Forseille

[1] John Adams, The Ker Family of Victoria, 1859-1967 (Vancouver: Holte Publishing, 2007); Arthur Tylor Richards, “(Re-)Imagining Germanness: Victoria’s Germans and the 1915 Lusitania Riot,” (MA Thesis, University of Victoria, 2012), 14.

[2] Richards, “(Re-)Imagining Germanness,” 24-48.

[3] Richards, “(Re-)Imagining Germanness,” 49-73.

[4] James Farney and Bohdan S. Kordan, “The Predicament of Belonging: The Status of Enemy Aliens in Canada, 1914,” Journal of Canadian Studies, 39.1 (2005).

[5] Richards, “(Re-)Imagining Germanness,” 95-97.

[6] See for further discussion of whiteness and race in British Columbia prior to WWI: Patricia Roy, White Man’s Province: B.C. Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1988).

Sources:

Adams, John. The Ker Family of Victoria, 1859-1976. Vancouver: Holte Publishing, 2007.

Farney, James and Bohdan S. Kordan. “The Predicament of Belonging: The Status of Enemy Aliens in Canada, 1914.” Journal of Canadian Studies, 39.1 (2005).

Richards, Arthur Tylor. “(Re-)Imagining Germanness: Victoria’s Germans and the 1915 Lusitania Riot.” MA Thesis, University of Victoria, 2012.

Roy, Patricia. White Man’s Province: B.C. Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1988), 267-268.

Further Reading:

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 2nd Edition. London/New York: Verso Books, 2006.

Fine, Michelle, Lois Weis, Linda Powell Pruit, and April Burns (eds). Off White: Readings on Power, Privilege, and Resistance. 2nd Edition. New York/London: Routledge, 2004.

Frankenberg, Ruth. White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993.

Kordan, Bohdan S. Enemy Aliens, Prisoners of War: Internment in Canada During the Great War. Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

Luciuk, Luboymyr. In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada’s First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-20. Kashtan Press, 2001.

Archival Sources: